Performance Anomaly of 802.11b

This research is conducted by Martin Heusse, Franck Rousseau, Cilles Berger-Sabbatel, Andrzej Duda on analyzing the performance of the IEEE 802.11b wireless local area networks. Degraded transmitting rate is caused by CSMA/CA channel access method.

Overview

The performance of the IEEE 802.11b wireless local area networks have degraded performances when some mobile hosts use a lower bit rate than the others, which is caused by CSMA/CA channel access method. When one host changes it modulation type which degrades bit rate, it occupies the channel for a longer time, causing other hosts still using higher bit rate to be penalized. The paper Performance Anamoly of 802.11b analyzes how such anomaly works.

Transmission Overhead

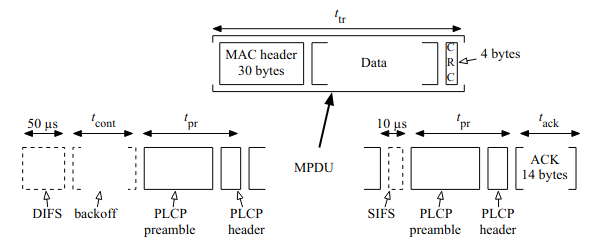

Consider there is only a single host in a 802.11b cell transmitting a single data frame. The overall transmission time is expressed as:

$$T = t_{tr} + t_{ov}$$

where the constant overhead

$$t_{ov} = DIFS + t_{pr} + SIFS + t_{pr} + t_{ack}$$

The transmission process can be represented by the graph

When there are multiple hosts attempting to transmit, a host will execute the exponential backoff algorithm - it waits for a random interval to avoid saturating the channel, resulting in extra time spent in the contention procedure:

$$T = t_{tr} + t_{ov} + t_{cont}(N)$$

Finally, the useful throughput obtained by a host depends on the number of hosts:

$$p(n) = t_{tr} / T(N)$$

This indicates the useful throughput is smaller than the nominal bit rate and largely depends on the number of competing hosts.

Anomaly

Assume there are \(N\) hosts, \(N-1\) hosts use high transmission rate \(R=11\)Mb/s, one hosts transmits at rate \(r=5.5\), \(2\), or \(1\) Mb/s. We can deduce the transmission time of the fast ones:

$$T_f = t_{ov}^{R} + \frac{s_d}{R} + t_{cont}$$

The transmission time of the slow host is:

$$T_s = t_{ov}^{R} + \frac{s_d}{r} + t_{cont}$$

The short term behavior of CSMA/CA is shown to be not fair, thus we have

$$U_f = \frac{T_f}{(N-1)T_f + T_s + P_c(N)\times t_{jam} \times N}$$

\(t_{jam}\) is the average time spent in collisions, calculated between the all possible pairs between the fast hosts and the slow one:

$$t_{jam} = \frac{2}{N}T_s + (1 - \frac{2}{N})T_f$$

The throughput at he MAC layer of each fast hosts is:

$$X_f = U_f \times p_f(N) \times R$$

given that:

$$p_f(N) = \frac{s_d}{RT_f}$$

We apply the same process for the slow host, given \(p_s(N) = \frac{s_d}{rT_s}\), what we get eventually is:

$$X_f=X_s = X$$

This key point here is that the fast hosts transmitting at the higher rate R obtain the same throughput as the slow host transmitting at the lower rate.

Simulation and Measurement Results

In general, the experimental value of \(P_c(N)\) seems to match the theory model. One thing the paper could illustrates better is to show how experimental value matches the equation as the number of hosts increases. The average and cumulative throughput value also seems reasonable compared to the expression discussed before.

The throughput is measured using three different tools: netperf, tcpperf, and udpperf. This idea of duplication makes the data collected more reliable and persuasive, which is especially useful in benchmarking since the results can be sensitive to environmental variable changes.

The presented results justify the statement made in the paper. For example, the measured TCP throughput for two hosts is shown to degrade as time passes:

One thing the paper can articulate more is how this seemly periodic pattern is related to the model. Another concern is the number of device used to conduct these experiments. The number of devices used seems to be much smaller than what would be in real-world scenario. It will be interesting to see how the performances are affected with a lot devices competing for a channel. This can be further extended to measuring performances with multiple devices having lower bit rate, which is more likely to capture real-world use cases. The potential performance impact is not clear given the present measurement.

The paper also claims the useful throughput strongly depends on the number of competing host. More data related to how the number of hosts is related to performance impact will make this paper more interesting. It may be hard to achieve as many papers resort to simulation.

This paper has made improvements over previous work in that it studies the performance of 802.11 WLANs, with one host having lower bit rate, whereas many other assume that all hosts communicate using the same bit rate. This is a step forward to capture more realistic situations. Overall, the paper does a good job in terms of proving its point. It captures the most critical information and it’s easy to follow the concept. However, the neat structure can make readers without sufficient background to spend more time catching up since the background section may not be enough for starters.

Conclusion

Overall, this paper brings novel approach to analyze the performance of 802.11 WLANs with varying bit rate. It brings new insights into studying the 802.11 standard. The paper focuses on TCP and UDP protocols. Applying the method discussed in paper to a lesser known protocol such as DCTCP can yield more insights into the different protocols can affect the throughput. Another direction is to generalize this model to multiple bit rate degrading and study their behaviors.

The bit rate used in the paper also seems to be pretty low compared to modern standards. With the introduction of 5G network, the bit rate becomes a lot higher, it will be interesting to see how extremely high bit rate can affect the performance of 802.11.