A Little Review on Barrelfish Memory Managements

The memory management has been mentioned numerous times and still remains huge topic. virtual vs. physical memory, physical frame allocation, MMUs, page faults, address space layout, and demand paging and swapping are familiar terms for every undergrad in college. In monolithic kernels such as Linux, much of the functionality is handled in kernel. However, there are OSes, such as Barrelfish, that takes a different approach by pushing these functionalities to user space. Many concept here will thus be borrowed from the Barrelfish OS. I also borrow some materials from the main pdf from Barrelfish course materials provided by Professor Simon Peter.

Memory Management in General

Microkernels like L4, Mach, Chorus, and Spring, trapped page faults in the kernel but then reflected them up to other processes which carried out the actual page fault handling. This was done on a per-region basis, so each area of virtual memory was associated with some paging server. Memory objects could be shared between different processes and mapped differently in different address spaces.

Such abstraction means that what happens when a page fault happens is entirely dependent on the code in the user-level pager. This design is highly extensible since it’s all user code and thus isolated, which means that if a user-level pager crashes, there’s a good chance the rest of the OS can continue quite happily since much of the functionality is moved away from the kernel.

However, moving functionality out of the kernel an important question: if user-space processes can manipulate virtual address spaces, how can we make sure that one user’s program can’t manipulate another address space and memory? Here we will introduce the concept of capabilities.

Capabilities

Capabilities are introduced to solve the access control problem in operating systems. Access control is the problem of specifying, and enforcing, which subjects (or principals) can perform particular actions on particular objects in an operating system.

The Barrelfish documentation does a good job illustrating capabilities: abstractly, access control can be thought of as a matrix, which represents all possible combinations of operations in the system. Each row of the matrix represents a different subject, and each column represents a different object. Each entry in the matrix contains a list of permissible actions.

Thus, we have two targets to emphasis: the subject and the object. The ACL(access control list) focuses on the object being operated on.

A good example will be whenever you enter ls -a in a Linux terminal, you will get list of entries specifies the attributes of a file. Here the attributes represent how a object (in this case, a file) may be accessed.

On the other hand, a capability can be thought of as a “key” or “license”. It is an unforgettable token which grants authority. Possession of a capability for an object gives the holder the right to perform certain operations on the object.

A good example will be the file descriptor in Linux. A file is accessed through its file descriptor. Here the file descriptor serves as the “key” to gain access to the file itself. Capabilities provide fine-grained access control: it is easy to provide access to specific subjects, and it is easy to delegate permissions to others in a controlled manner.

Note that to be correct, any capability representation must protect capabilities against forgery. Capabilities can be implemented in various ways such as tagged capabilities, sparse capabilities, or partitioned capabilities. In Barrelfish we used the partitioned capabilities.

In partitioned capabilities, the kernel ensures that memory used to store capabilities is always separated from that used by user processes to store data and code, for example by using the MMU or ensuring that capability memory is only accessible in kernel mode. The OS maintains the list of capabilities each user principal holds (the clist), and explicitly validates access when performing any privileged operation. Thus, whenever the user accesses memory, the operation can only be done through the resources’ corresponding capability. For example, one can map a page frame in the page table page through functions calls with only capabilities.

Caprefa->install(Caprefb, slot, flags)

Capabilities in Barrelfish

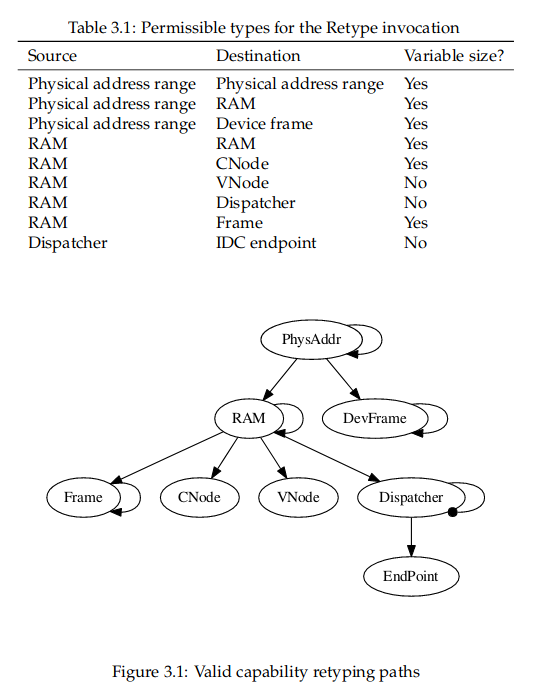

According to Barrelfish documentation, all memory in Barrelfish (and some other system resources which do not occupy memory) is described using capabilities. Capabilities are typed, and capabilities can be retyped by users holding them according to certain rules and restrictions. The official documentation has very good explanation on the capability management in Barrelfish. Here is the permissible types for the retype invocation capability retyping:

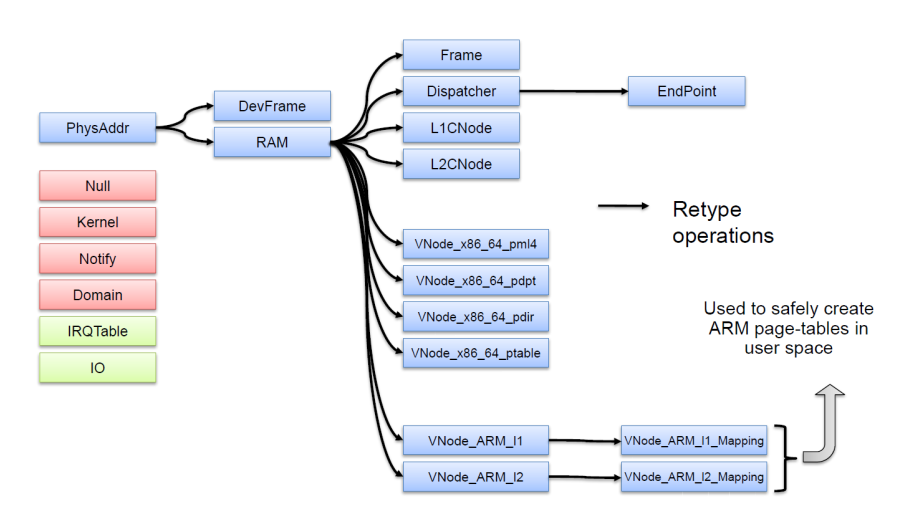

Capabilities referring to memory regions. Capabilities can also be split, resulting 2 new capabilities of the same type, one for each half of the region. Some of the more important capability types in Barrelfish are shown in figure below. The picture is from the Barrelfish manual provided in CS378 Multi-core class by Simon Peter:

Allocation and management of physical memory is achieved by retyping and splitting operations on capabilities. For most kernels, the implementation is to constantly allocate and deallocate memory for a wide variety of purposes, much as any large C program relies heavily on malloc and free.

The problem is what the kernel should do when this runs out. The current solution in Linux is little more than “kill a random process and reclaim its memory”, which can be a problem for system stability. In Barrelfish, all kernel objects are actually allocated by user programs. If a user process wants to create another process (or dispatcher in Barrelfish parlance), it has to get a capability to a DRAM area of the right size, retype this capability to type Dispatcher, and hand this to the kernel. This will be covered in later posts. To access different types of memory resources, the corresponding capability has to be retyped to the right type.

More On Implementation

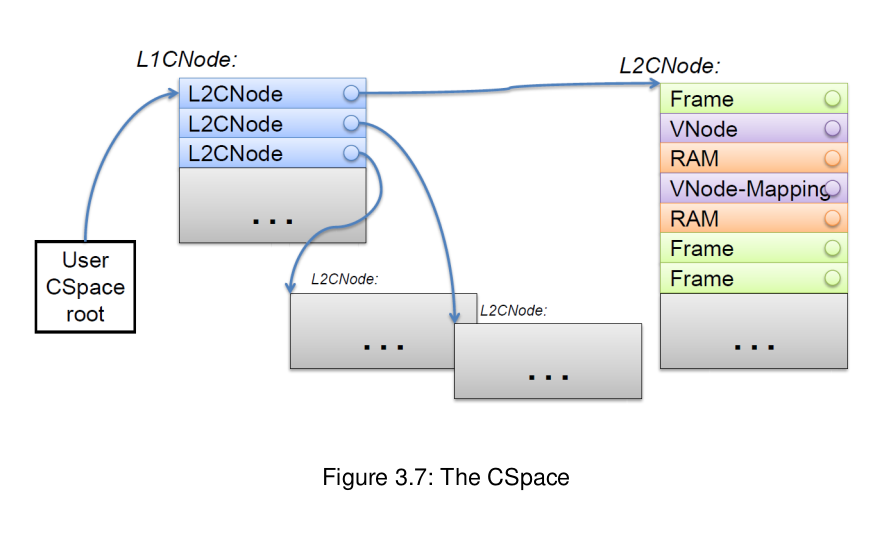

In Barrelfish, every capability resides in a slot in a CNode, so a pair (CNode, slot) would identify a capability. It is important to point out that the CNode is another capability itself. Each process in Barrelfish has a CSpace which is structured as a two-level table. So there are actually two different CNode capability types - one for the first level of the table, and one for the second. Every process has, within its “dispatcher control block”, a pointer to the top-level or root CNode which the kernel can traverse.

A capability reference in Barrelfish is very similar to VA: the first few bits can represent an index into the first level L1CNode, while the next few bits refer to a slot in a CNode referred to by the capability in the L1CNode slot. Here is a picture from the main pdf showing how the the CSpace is represented in Barrelfish:

Thoughts on Design Decisions

Even though it is pretty straight forward to understand the CSpace structure, the actual implementation is a lot more complicated than that. Since the CSpace is not directly accessible by user space program, there are additional data structures used to keep track of available memory resources.

In our implementation, the user process keeps a doubly linked list of struct mmnode to indicate the memory available for allocation. Each element in the free list tracks the information corresponding to one capability. However, there is a big problem with this seemingly simple implementation. Every time we allocate a practical memory space from the memory region, a new capability is created while the old capability still remain in the physical memory pointing to a memory range before the allocation happens. Therefore, the old capability would cover extra memory spaces that are already allocated and managed by other capabilities.

To solve this problem, we maintain the allocation information in the struct mmnode each time an allocation occurs. If a capability covering physical address space from 0 to 100 is requested for 20 units of memory space, then the memory available for the next allocation would be from 20 to 100 even though the capability itself still manages 0 to 100. By restricting subsequent accesses only to the new memory range, the old capability can still be kept around and used later for retyping.

Another Problem emerges when we try to free a memory. Since everything is managed by capabilities, freeing a piece of memory also involves managing the capability responsible for the memory. So an intuitive thought could be whenever a memory space is freed, the corresponding capability is merged back to a piece of memory adjacent to it, managed by a different capability.

However, since capabilities can not be merged, an alternative choice would be to simple destroy it during free. However, this is even a bigger problem in Barrelfish.

Imagine the scenario where capability A is partially allocate from memory space 30 to 100. Later on another memory is freed and that piece of memory is managed by capability with base 100 and size 20, so the memory range covers 100 to 120, which indicates these the two capability could be “merged”.

In this case, if the first capability is destroyed, all children of the first capability will also be destroyed, thus the already allocated memory from 0 to 20 will be thrown away, which is not desired. If the second capability is destroyed, the first one will also be destroyed to create a new capability covering 20 to 120, which will still results in the destruction of capability A.

Our assumption here is that the parent or root capability is never destroyed when added to the free list. Whenever a capability needs to be freed, the memory manager is responsible to make sure the capability is only merged with another capability from the same parent capability.

This is done by creating another list of nodes that tracks all parent capabilities. It is only added when the memory manager adds new capabilities to the free list. After the user initializes free, the memory manager actually creates a new free struct mmnode first, then it find the node’s parent node, copying the parent’s capability and attributes to the newly created node with updated offset to indicate that the memory hasn’t been freed yet.

After that, the memory manager insert the node into the free list. If the memory manager finds out that there are capabilities adjacent to the just-added node, then we simply need to update the attributes of the corresponding mmnode to indicate that merging succeeds. The old mmnode is simply thrown away.

The advantage of this implementation is that root or parent capabilities are kept around and the next retype will be fairly simple. The implementation is also very straightforward.

There is of course more efficient solution than a linked list. For example, Linux uses both linked list and red-black tree to store thread information. The redundant data structures can be used in different scenarios when appropriate. However, we only use this simplified version to prove our concepts. Optimizations vary but the general concept still works pretty well.